Lake Superior, the largest freshwater lake in the world, has long been a graveyard for ships. Its volatile weather, deep waters, and rocky shores have claimed countless vessels, earning it a fearsome reputation among mariners. One of these unfortunate ships was the Huronton, a steel bulk freighter that met its fate in 1923. Exactly 100 years later, its wreck was rediscovered, shedding new light on its tragic final moments and the challenges of navigating the Great Lakes.

The Great Lakes, a series of massive freshwater bodies spanning the border between the United States and Canada, are a critical part of North American commerce. With their vast resources and intricate waterways, they have long served as vital routes for transporting raw materials. In particular, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, rich in iron ore, became a hub of mining and shipping operations in the 19th century. Freighters, or "lakers," carried these heavy loads across the lakes, braving unpredictable weather and treacherous waters.

Lake Superior, the largest of the five Great Lakes, holds more water than the other four combined. It is not only vast but also dangerous. Its waters are icy cold, its depths reach over 1,300 feet, and its weather can shift rapidly from calm to stormy. Sailors often faced hurricane-force winds and waves that rival those of the ocean. For ships like the Huronton, these conditions could be lethal.

The Huronton, a 138-foot steel bulk freighter, was one of the many vessels that navigated these perilous waters. On October 11, 1923, it was traveling across Lake Superior after delivering a load of iron ore. The freighter was light and moving quickly, a dangerous combination given the conditions that day. A dense fog, worsened by smoke from nearby forest fires, reduced visibility to almost nothing. Despite the risk, the ship pressed on.

Unbeknownst to the crew of the Huronton, another freighter, the Cetus, was also navigating the lake. At 416 feet long and heavily laden with ore, the Cetus was slower but no less dangerous. Both ships were traveling too fast for the poor visibility. The inevitable happened: the bow of the Cetus collided with the port side of the Huronton, creating a massive hole in its hull.

The collision was catastrophic. Initially, the two ships were stuck together, but as the Cetus pulled away, the Huronton began taking on water rapidly. Its fate was sealed. Recognizing the danger, the captain of the Cetus made a bold decision. He maneuvered his ship to re-engage the Huronton, temporarily plugging the hole. This desperate act bought just enough time for the crew of the Huronton to evacuate. All 17 crew members safely transferred to the Cetus.

However, in the chaos of the evacuation, the Huronton’s mascot, a bulldog, was left behind. Tethered to the ship, the dog faced certain doom as the freighter sank. In a moment of incredible bravery, First Mate Dick Simpell leaped back onto the sinking ship. The Huronton was listing dangerously, and water was pouring in, but Simpell was undeterred. He untied the frantic dog and returned to the Cetus just in time. Moments later, the Huronton slipped beneath the waves, vanishing into the depths of Lake Superior.

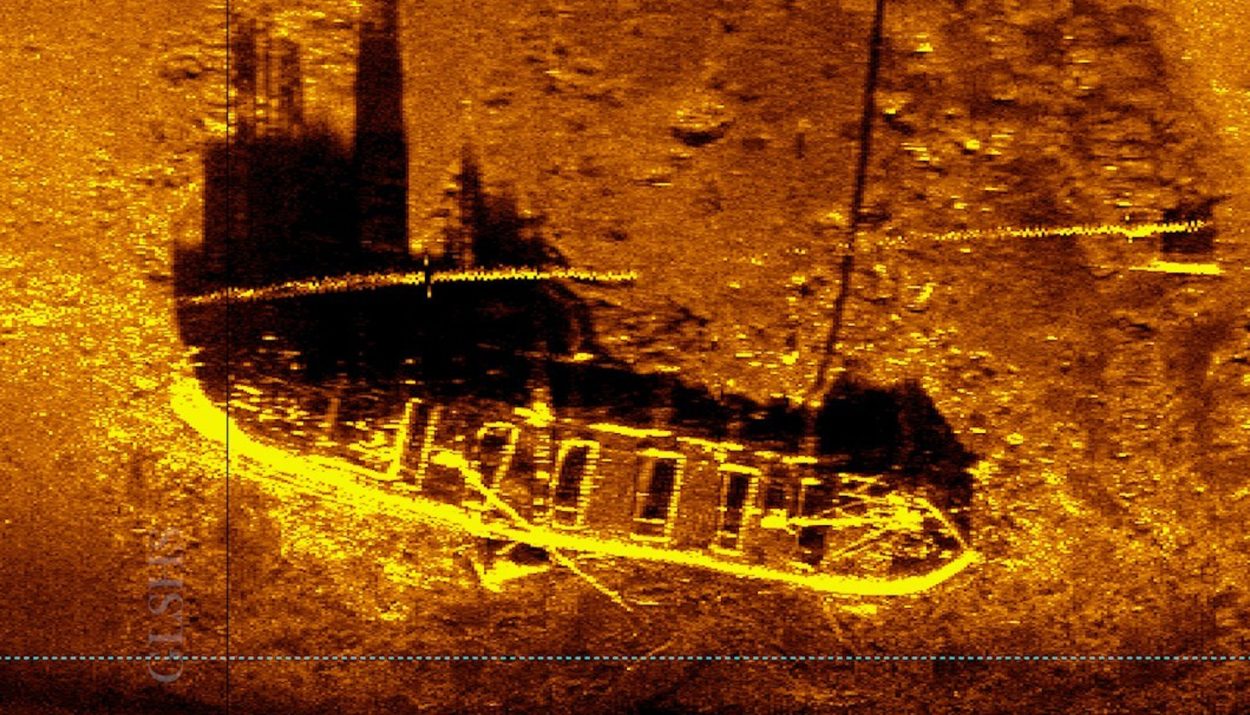

For years, the story of the Huronton remained a cautionary tale, a reminder of the Great Lakes' unforgiving nature. Its final resting place, however, was a mystery. In 2023, exactly 100 years after the freighter sank, the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society set out to locate and document shipwrecks in Lake Superior. Using side-scan sonar technology, they scoured the lakebed near Whitefish Point, an area known for its steep 800-foot drop-off.

The sonar detected a linear anomaly, a sign that something man-made lay beneath the surface. To confirm the find, the team deployed a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) equipped with cameras and lights. The images sent back from the ROV revealed the Huronton, remarkably well-preserved after a century underwater. The discovery was announced on October 11, 2023, exactly 100 years to the day after the ship sank.

The rediscovery of the Huronton was not only a historical milestone but also a reminder of the challenges facing underwater cultural heritage. Invasive species, particularly quagga and zebra mussels, pose a significant threat to shipwrecks in the Great Lakes. These mussels attach to submerged structures, forming dense colonies that can cause physical damage and accelerate deterioration. While Lake Superior has so far been spared the worst of these infestations, the presence of these invasive species is a growing concern.

The cold, deep waters of Lake Superior have helped preserve the Huronton and other shipwrecks, but this natural preservation is under threat. Researchers and preservationists are racing against time to document and protect these underwater relics before they are lost forever. The discovery of the Huronton underscores the importance of these efforts and the rich history hidden beneath the surface of the Great Lakes.

The discovery of the Huronton in 2023 was a triumph not only for maritime historians but also for the dedicated team at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society (GLSHS). The precise timing of the find—on the 100th anniversary of its sinking—added an almost poetic resonance to the event. Bruce Lynn, the director of the GLSHS, reflected on the significance of the moment. “Finding any shipwreck is exciting,” Lynn remarked, “but to find one exactly 100 years later is truly extraordinary. To think that we’re the first human eyes to see this vessel since it disappeared is humbling and awe-inspiring.”

The Huronton lay approximately 800 feet beneath the surface, in a part of Lake Superior where the lakebed drops steeply into a deep abyss. Its intact condition was striking. Unlike wrecks in other Great Lakes, which are often encrusted with invasive mussels or severely corroded, the Huronton appeared almost frozen in time. The cold, oxygen-deprived waters of Lake Superior had acted as a natural preservative, shielding the wreck from much of the decay that might have otherwise occurred. Even details such as rivets on its steel hull and remnants of its cargo hold were visible, providing researchers with a treasure trove of information about early 20th-century shipbuilding and maritime practices.

This discovery highlights a critical element of Great Lakes maritime history: the role of freighters like the Huronton in shaping the industrial growth of North America. By transporting vast quantities of iron ore, coal, and other raw materials across the region, these vessels were integral to the steel industry and the broader economy. The Huronton itself was part of this system, serving as a crucial link in the supply chain that fueled the industrial boom of the early 20th century. Its story is a window into a bygone era of heavy industry and relentless innovation.

However, the Huronton’s rediscovery also serves as a stark reminder of the dangers inherent in maritime transport on the Great Lakes. Even today, with modern navigation tools and weather forecasting, ships face significant risks on Lake Superior. The sudden storms and towering waves that sailors have long feared remain a formidable challenge. For the crews of early freighters, who navigated with rudimentary equipment and often under intense pressure to meet schedules, these risks were even greater.

The Huronton’s ill-fated voyage in October 1923 encapsulates these dangers. The dense fog and smoke that blanketed the lake that day created a perfect storm of hazards. Visibility was severely impaired, and the speed at which both the Huronton and the Cetus were traveling left little room for error. The subsequent collision and rapid sinking of the Huronton underscore the precarious nature of maritime navigation in such conditions.

Yet amidst the tragedy of the Huronton’s sinking, there is also a tale of courage and humanity. The quick thinking of the Cetus’s captain, who re-engaged his vessel with the sinking freighter to allow the crew to evacuate, likely saved 17 lives. The bravery of First Mate Dick Simpell, who risked his life to rescue the ship’s dog, is a testament to the bond between humans and their animal companions, even in the direst circumstances. These moments of heroism resonate deeply, reminding us that even in the face of disaster, acts of kindness and courage can shine through.

The Huronton’s story also carries an environmental message, particularly in the context of the threats facing Great Lakes shipwrecks today. Invasive quagga and zebra mussels, which first appeared in the Great Lakes in the 1980s, have spread rapidly and wreaked havoc on underwater ecosystems. These mussels attach themselves to submerged structures, including shipwrecks, and feed on plankton, disrupting the natural food chain. Over time, their colonies can become so dense that they physically damage the wrecks, reducing once-pristine relics to rubble.

While Lake Superior has so far escaped the worst of these infestations, thanks to its colder and less nutrient-rich waters, the presence of these mussels is a growing concern. Shipping vessels inadvertently spread the invasive species between lakes, and measures to prevent their spread have had limited success. The GLSHS and other preservation organizations are acutely aware of the urgency to document and study shipwrecks like the Huronton before they are irreparably damaged.

Efforts to protect these shipwrecks extend beyond simply cataloging them. Researchers and conservationists are exploring innovative methods to mitigate the impact of invasive species, from targeted removal techniques to the development of protective coatings for wrecks. At the same time, public awareness campaigns aim to educate people about the importance of preserving underwater cultural heritage and the ecological challenges facing the Great Lakes.

The rediscovery of the Huronton also draws attention to the broader legacy of shipwrecks in the Great Lakes. Each wreck tells a unique story, offering insights into the technological, economic, and social history of the region. From passenger steamers and fishing boats to massive freighters like the Edmund Fitzgerald, these vessels are time capsules that connect us to the past. Documenting and studying them is not just an act of historical preservation—it is a way of understanding the forces that shaped the Great Lakes and the communities that depend on them.

For the team at the GLSHS, the discovery of the Huronton is a reminder of why their work matters. Every summer, they embark on expeditions to locate and document shipwrecks, driven by a passion for uncovering the stories hidden beneath the waves. Their work is painstaking and often unpredictable, but the rewards are immense. Each new discovery adds to the collective knowledge of Great Lakes maritime history, ensuring that these stories are not forgotten.

The Huronton, now resting peacefully on the lakebed, stands as a symbol of resilience and remembrance. Its rediscovery 100 years after it sank is not just a triumph of modern technology and determination—it is a poignant reminder of the enduring power of history. As researchers continue to explore the depths of Lake Superior, they carry forward a legacy of curiosity and preservation, ensuring that the stories of these lost vessels will continue to inspire future generations.

0 commentaires: